Asthma is an inflammatory disease of the airways, characterised by variable airflow obstruction presenting clinically as cough, wheeze and dyspnoea. With a prevalence of 4-12% in women of childbearing age, it is the most common chronic respiratory condition encountered in pregnancy. Hormonal, physiological and mechanical changes during pregnancy can manifest as a change in asthma control. The clinical course of asthma in pregnancy is difficult to predict however and can vary significantly between patients. Those with severe asthma pre-conceptually are more likely to deteriorate during pregnancy compared to those with mild disease.

Written by Dr Margaret Gleeson, Clinical Research Fellow in Beaumont Hospital/RCSI, Dr Claire McCarthy, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, Rotunda Hospital and Prof Dorothy Ryan, Consultant Respiratory Physician in Beaumont Hospital/RCSI

For the majority of women, asthma poses no adverse risk to pregnancy outcome. However compelling evidence suggests that those with poorly controlled disease or repeated exacerbations in the antenatal period are at risk of significant materno-fetal complications including pregnancy loss, pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage, low birth weight and preterm birth. The goals of asthma management in pregnancy are the same as in non-pregnant patients: to control symptoms, preserve lung function, prevent and treat exacerbations and minimise medication side-effects. Pharmacists play a crucial role facilitating safe, effective and informed management of asthma during pregnancy, working collaboratively with the multidisciplinary team to optimize treatment outcomes.

The most common cause of deterioration in asthma control is due to poor compliance with medication. Expectant mothers may perceive there to be a risk associated with asthma medications, specifically corticosteroids and less so with bronchodilators. Almost 50% of women reduce or discontinue their medications early in pregnancy without specialist input, putting them at risk of complications. A review of prescriptions in the first trimester compared to the preconception period saw a reduction of 13%, 23% and 54% of short acting beta agonists (SABA), inhaled (ICS) and oral corticosteroids (OCS) respectively.

Evidence to date on medication safety in pregnancy and lactation is limited by a lack of randomised controlled trials in this cohort, however clinical practice has been longitudinally observed and robust data retrospectively reviewed. Research examining medication safety during pregnancy can also be influenced by the severity of asthma where increased medication use and above standard dosing may contribute to resultant complications.

MANAGEMENT

Diagnosis

Ideally patients should have an asthma diagnosis confirmed and optimised pre-conceptually. Asthma symptoms of cough, wheeze and shortness of breath are highly non-specific. There should be a pattern of variability in symptoms and response to asthma therapies such as ICS, OCS or SABA. Thus, before and during pregnancy exclusion of alternative causes of asthma-like symptoms of wheeze, dyspnoea and cough (e.g. reflux, rhinitis, obesity and cardiovascular disease) is important.

Monitoring during Pregnancy

Estimating severity, disease monitoring and assessment of treatment response throughout pregnancy improves outcomes. Patients with poorly controlled asthma (e.g persistent symptoms despite adherence to standard therapy, hospitalisation or OCS use in the 12 months prior to pregnancy) should be followed closely by a multi-disciplinary team including an obstetrician and respiratory physician. Education should include inhaler technique, peak flow monitoring and action plan provision. Recent guidelines recommend regular review for patients to facilitate reassurance, further education and treatment manipulation. This also provides an opportunity to support smoking cessation and vaccination to minimise risk factors for poorly controlled asthma.

Convincing evidence to date repeatedly indicates that the potential risks of untreated asthma far outweighs any theoretical risk or speculative concerns associated with the use of asthma medications during pregnancy.

Role of the pharmacist

Counselling patients on medication use, compliance and safety is of utmost importance. Involvement of a clinical pharmacist in this process improves patient’s understanding and experience of asthma in pregnancy and in some centres pharmacy services are included as standard of care.

The pharmacist often serves as the initial point of contact for patients experiencing asthma symptoms. This early interaction can be pivotal, as it may reveal either a diagnosis of asthma, indicate poorly controlled disease or suggest an alternate unrelated pathology. All scenarios are of concern and signal the need for further medical evaluation.

Pharmacists assist in optimizing maternal asthma to achieve optimal control while minimizing potential risks. This may involve titrating medication doses, switching to safer alternatives, or incorporating non-pharmacological approaches such as proper inhaler techniques and trigger avoidance. Red flags include excessive collection of reliever medications (e.g. SABA) and discontinuation or reduced use of controller (ICS) medications.

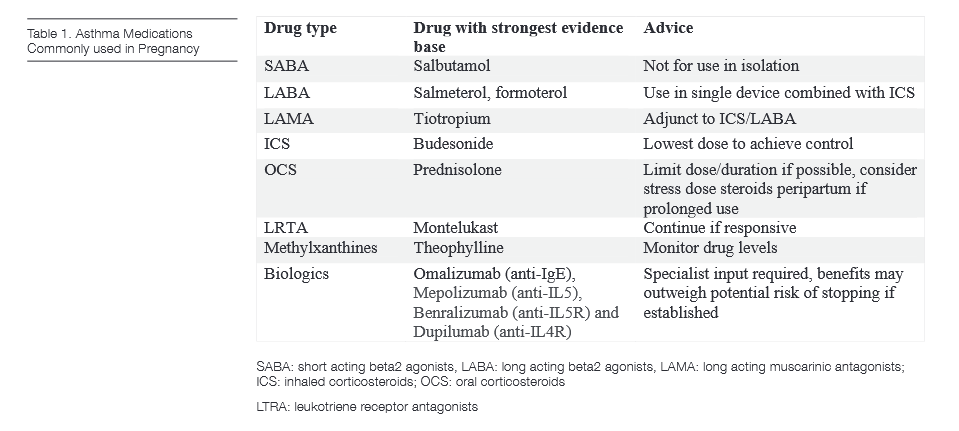

ASTHMA MEDICATIONS

Bronchodilators

Short acting beta2 agonists (SABA) are primarily used as a reliever therapy. As in non-pregnant asthma, their use in isolation is no longer recommended. Salbutamol is the preferred agent as it has been most extensively studied but terbutaline may be used if already prescribed. Following inhalation, salbutamol is essentially undetectable in the blood however small amounts may be absorbed systemically via oral deposition. There is no evidence to date that SABA exposure is associated with fetal malformations.

Longer acting beta2 agonists (LABAs) should be used in fixed combination with ICS for control or relief of asthma symptoms. Studies on the use of LABAs alone are lacking with pharmacologic and toxicologic profiles largely extrapolated from that of SABAs. To date these have not been shown to cause any significant harm and should be continued in those already established on treatment. Salmeterol and formoterol are the most widely used with salmeterol the drug of choice if needed based on more readily available longitudinal evidence. There is limited human experience with newer UltraLABAs such as olodaterol and vilanterol but were considered low risk in animal models.

Anti-cholinergics

Short acting anticholinergic agents are used as an alternative reliever medication to SABAs and ipratropium can be used if indicated. Long acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) are not considered first line treatment in asthma and there is limited experience with their use in human pregnancy. Tiotropium is the most commonly prescribed in addition to ICS/LABA for those sub-optimally controlled. Animal studies indicated negative outcomes at high doses however there have been no concerns for adverse effects in those who continued during pregnancy.

Corticosteroids

As in non-pregnancy asthma, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay of asthma therapy. ICS have been shown to reduce exacerbations which is essential to prevent fetal hypoxia and improve lung function during pregnancy. For some formulations there is little to no data in pregnancy, however studies to date have not identified a risk to the foetus with ICS and their use has been supported in subsequent systematic reviews. Budesonide, with the most gestational data including a large study in over 2,000 pregnant women with no increased risk of fetal abnormalities, is the recommended agent if newly required in pregnancy. If asthma is controlled on an alternative ICS pre-pregnancy, particularly if severe disease, it should be continued. Where possible the lowest dose of ICS should be used to maintain disease control. High-dose ICS will absorb systemically and could mimic oral corticosteroids (OCS) side-effects (see below).

OCS in asthma are prescribed for acute exacerbations and less frequently as maintenance therapy in severe refractory asthma. Whilst evidence in asthma during pregnancy is limited, OCS have been used in pregnancy for many other inflammatory and autoimmune conditions from which relevant data can be extrapolated. Some studies have reported a threefold increase (0.3%) in the risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate compared to the background population (0.1%) when exposed to OCS in the first trimester. Prematurity, pre-eclampsia and low birth weight have also been reported but not consistently across studies in humans . Prednisolone is the drug of choice as the predicted level in fetal blood is only 10% that of the mother, much less than dexamethasone and hydrocortisone. Adverse events can be minimised by limiting the dose and duration of exposure.

Women taking regular OCS (>7.5mg for two or more weeks) are potentially at risk of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression and thus strong consideration should be given here to administering a “stress dose” of parenteral steroids in the peripartum period. Prednisolone can cross the placenta and while initial case reports have suggested supra-physiological maternal OCS use in the later stages of pregnancy can be associated with neonatal adrenal insufficiency, a further retrospective review found no prolonged or clinically significant adverse outcomes as a result of their use. Drug levels for prednisolone in breast milk peak two hours after ingestion but with very low detectable levels. There have been no adverse effects reported in breastfed infants and thus recommendations to delay breastfeeding are not necessary in standard dosing regimens.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LRTA) are not first line and rarely prescribed alone for the treatment of asthma so specific safety data on their use in pregnancy is lacking. Animal studies have not shown any risk to the fetus and prospective observational studies in humans did not show an increased risk of malformations compared to the background population. Initial studies suggesting adverse pregnancy outcomes with use later in pregnancy have not been reproduced and may be confounded by asthma control. The Asthma and Pregnancy Working Group and British Thoracic Society guidelines suggest that they be continued if already established on treatment with a significant improvement in asthma control demonstrated prior to pregnancy, with most evidence available for Montelukast.

Theophylline

At recommended doses these agents can be used safely in pregnancy with no evidence for congenital abnormalities. Data on pregnancy outcomes is largely conflicting but adverse pregnancy outcomes have not been consistently proven in human studies. Theophylline can be used as a regular preventer as an add-on therapy. Ideally monthly drug levels should be monitored during pregnancy as circulating binding proteins are reduced in pregnancy and free drug levels can increase. Above standard doses were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in animal studies. Theophylline crosses the placenta and so its use in the third trimester can be associated with therapeutic serum levels in the foetus. Transient neonatal withdrawal symptoms can occur following delivery, including irritability, tremor, tachycardia and vomiting. Theophylline has a low concentration in maternal breast milk and is safe in nursing mothers, with slower release preparations suggested to minimise risk of infant irritability.

ITS Flashcard – Asthma Medications in Pregnancy accessible via this QR code

Biologics

The advent of targeted monoclonal antibody therapy licenced for severe asthma has been revolutionary. As yet, evidence on their use in pregnancy is preliminary though encouraging. Drug properties suggest low risk to breastfed infants, however limited data advises caution in premature neonates and in the early neonatal period. Delaying the first postpartum dose to two weeks after delivery can minimise transfer to the infant.

Currently there is most evidence for the anti-IgE biologic Omalizumab (Xolair) based on the Xolair Pregnancy Registry (EXPECT). The conclusion of this registry study was that adverse outcomes in those exposed to this monoclonal antibody before or during pregnancy such as congenital malformations, low birth weight and premature delivery were similar to those found in asthma patients not taking it.

Newer monoclonal antibodies used in asthma including Mepolizumab (anti-IL5), Benralizumab (anti-IL5R) and Dupilumab (anti-IL4Rα) have scant safety data in pregnancy to date. Benralizumab administered at maximum doses during pregnancy in animal studies showed no adverse effects. Mepolizumab also did not have any embryotoxic, teratogenic or adverse effect on neonatal growth when used during pregnancy or nursing.

Discontinuation of biologic therapy may lead to a deterioration in asthma control and thus benefits may outweigh any potential risks. There is a lack of consensus on commencing or continuing biologic therapy for severe asthma during pregnancy, and decisions are made by a specialist severe asthma team on a case by case basis.

CONCLUSION

Managing asthma during pregnancy requires a delicate balance between controlling maternal symptoms and minimizing potential risks to the pregnancy. With a multidisciplinary approach including collaboration with clinical pharmacy, expectant mothers can receive personalized care that prioritizes both maternal and fetal health.

References available on request

Acknowledgments to Ms Joanna Carroll, Pharmacist, Beaumont Pharmacy Department and Dr Fergal O’Shaughnessy, Pharmacist, Irish Medicines in Pregnancy service/Rotunda Hospital.