In order to continue selling medicines to consumers after 9 February 2019, all actors within the European supply chain must comply with new legally binding rules arising from the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD). Irish Pharmacy News has been finding out what the directive is, why it matters – and importantly – what it means for you.

In 2016, more than 600,000 dosage units of false or substandard medicines were detained by Irish authorities. According to Ireland’s Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) these items – mostly bought online – pose a real and substantial risk to people’s health and to their lives. Health regulators and other authorities are having to innovate to keep up with rogue actors and criminals and it is estimated that globally up to 10% of medicines are substandard or falsified (SF). In Africa and Asia, that figure rises to a startling 42%.

Dr Mariangela Simão is the assistant director-general for access to medicines, vaccines and pharmaceuticals at World Health Organisation (WHO). According to Dr Simão, “[s]ubstandard or falsified medicines not only have a tragic impact on individual patients and their families, but also are a threat to antimicrobial resistance, adding to the worrying trend of medicines losing their power to treat.”

The WHO stopped using the term ‘counterfeit’ in respect of unsatisfactory medicines in 2017 and instead adopted the phrase ‘substandard or falsified’ (SF). The new terminology captures a broader definition of what poor quality drugs are and accounts for products that although may be legitimate in terms of their ingredients, may not be acceptable due to incomplete, missing or falsified paperwork. The word ‘counterfeit’ has been restored in practical terms to meaning a trademark violation, as defined under trade rules on intellectual property at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Irish context

Lorraine Nolan is the CEO of the HPRA. Despite the prevailing attitude that falsified medicines are not really that big of a problem in Ireland when compared to other markets, the HPRA and other authorities are in a constant battle to reduce the number of SF items getting into the hands of Irish consumers and patients.

“It is a growing issue worldwide and in Ireland alone we detained over 600,000 illicit medicines in 2016 , with over one million being detained in 2017. National and international collaboration and the sharing of information has been a crucial factor in successfully curtailing exploitation and protection of our citizens from dubious and substandard products.”

Nolan welcomed the new measures, and acknowledged the different challenges faced by drug regulators around the world. The hope is that by closing the supply chain in Europe and other markets, patients everywhere will be protected from illicit traders. “[Regulators] are very aware of the potential for exploitation of our patients through the illicit supply of counterfeit and substandard medicines and health products. If we have these challenges in high income countries we can consider that it is even more challenging in the low and middle income countries.”

IPN spoke to the Head of regulation of medicines at the World Health Organisation, Emer Cooke, about these changes.

“It’s very rarely a single country problem but is something that goes across borders … [WHO] published a study on the socio-economic impact of substandard and falsified medicine last year and we reviewed 100 research articles which looked at the problem and we estimated the … cost to society was over $30 billion. These are rogue actors. Regulators are used to regulating the ‘good’ and these are the ‘bad’ and people will always find a way to try and cheat the system. But if we can raise awareness, if we can train regulators, if we can improve the laboratory systems I think we can do a lot better.”

IPN asked if the rationale behind the directive and the need for its implementation has been communicated effectively to dispensers in high income markets. “It is a problem everywhere. Strong regulatory systems can catch it better, but the falsified [medicines] directive is enabling better control. The thing that … maybe national and regional regulators haven’t been so good at is realising the connections that need to be made in a global marketplace. Problems tend to occur at the weakest link in the chain. When you’ve got a European system, how do you make sure this is working across all countries? You’ve got a global supply chain: what is happening to your imports? What is happening to your exports? I really think the directive is needed and I think Europeans will see the benefit of it.”

Protecting consumers

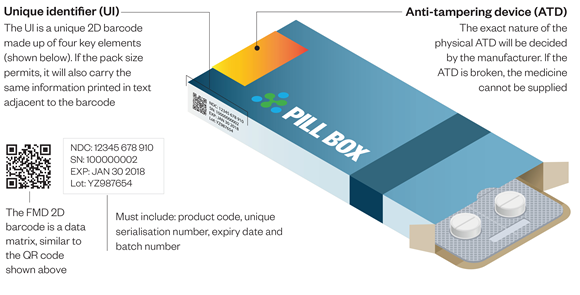

The Directive (which is an amendment to Directive 2001/83/EC) has been designed to more rigorously protect the pharmaceutical supply chain by closing it through the adoption of serialisation and verification measures and procedures. The final step, decommissioning, happens at pharmacy dispensary level, and is a vital component in ending exploitation opportunities for criminals who profit from SF drug products. Decommissioning happens when the pharmacist scans the 2D barcode containing the serial number at dispensary level and is satisfied that the product they are dispensing has been verified on the repository that is connected to the centralised European hub. When a pharmacist decommissions a pack, it will be marked on the system as having been dispensed and the serial number will no longer be available for use. The directive also requires all prescription medication packages to have a tamper-proof seal.

The Irish Medicines Verification Organisation (IMVO) was required by the directive to be established in advance of the compliance deadline. Tracelink is the world’s largest track and trace network for connecting the life sciences supply chain and are one of the 12 software partners working with IMVO to provide solutions. Brian Daleiden is the Vice President of Tracelink. He is on record explaining how the serialisation and verification procedures will operate in practical terms.

“The manufacturer needs to serialise drug product at the smallest saleable unit, and then they need to submit master data about that drug product and the serialisation information related to [it] to a central European hub. As the product moves into the supply chain, the primary responsibility for track and trace compliance then falls onto the dispensers – the pharmacies. Before they dispense the drug product that pharmacy needs to scan the barcode to verify a couple of pieces of information: first off, to verify the serial number was actually created and applied to a drug product; the second is to check to find out if there’s any adverse states that the drug product exists in. Maybe [it] was marked as stolen, or marked as potentially counterfeit. When the pharmacist scans the product they can get information that says that this could be a questionable drug product, not just that the serial number exists.”

Manufacturers in Ireland are currently shipping serialised products to markets in parts of the world that have already adopted similar measures to protect their drug product supply chain. Turkey is considered to be a pioneer in respect of serialising and tamper-proofing health products and Brazil, China, South Korea and the USA have followed suit.

Implications for Irish dispensers

After February 2019, anyone dispensing prescription medication will have to verify the product’s authenticity and decommission it from the IMVO repository before it can be supplied to the patient. There are a handful of exceptions (such as gases) and the directive does not apply to P or GSL items, with one exception, omeprazole gastro-resistant hard capsules. The legislation requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to meet the costs of establishing the national verification bodies, such as the IMVO in Ireland’s case, and pharmacists and wholesalers are similarly required to absorb whatever cost implications arise at dispensary level, such as through the purchase of essential equipment (i.e., scanners, software, hardware). IMVO is aiming to start connecting all end-users in early Autumn when the pilot project, which applies to 30 locations in Ireland, is completed.

Leonie Clarke is the General Manager at IMVO. She spoke to IPN about the huge amount of work that is going on behind the scenes to ensure compliance by the February deadline.

“A report on the pilot project in community pharmacy is expected to be made available from the IPU by the end of September and by then we expect to have written out to all 1800 pharmacies in the jurisdiction, explaining to them what is expected and how we intend to support them. Online training in the form of webinars will be made available and we also expect by that stage to be in a position to have collated a table of information indicating to pharmacists who they can contact if something goes wrong. Our partners in the IPU have been regularly updating pharmacists of the anticipated changes and we at IMVO have been focused on planning things out so that there is clarity for all users. We have also streamlined procedures within our own organisation to ensure a smooth on-boarding process. Our focus is to learn from the pilot project so that we are fully prepared for all the issues that could arise. We expect to be in a position to start ramping up communications with pharmacists when the results of the pilot project have been collated.”

IMVO website has the following information for pharmacies about what steps can be taken in advance of the requirements becoming legally binding next February:

- Identify where scanning will take place and what terminals need to be connected;

- Upgrade existing software systems to interact with IMVO repository and/or installing a standalone system;

- Implement necessary changes in work practices, procedures, etc.;

- Have scanners in place to read barcodes;

- Inform your team of what is happening and train relevant staff;

- Considering how anti-tamper device checks will be managed.

This report is part one of a three part series coming over the next few months.

Author: Áine Carroll