Pharmacy Management of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD)

60 Second Summary (GORD)

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is often a chronic condition involving the reflux of gastric contents back into the oesophagus, causing symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation.

- The incidence of GORD is increasing, with 25% of people reporting heartburn once per week and 5% with daily symptoms

• Genetics and lifestyle factors such as pregnancy, smoking, obesity, and diet are all involved in the development of GORD, the main mechanism being inappropriate relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter.

• GORD causes a variety of oesophageal and extraoesophageal symptoms, and important complications such as stricture, haemorrhage, Barrett’s oesophagus, and carcinoma.

• The aim of treatment is to relieve the symptoms of GORD and reduce the risk of recurrence and associated complications of GORD.

• Initial management of GORD involves lifestyle modifications and OTC medications including alginates and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

• Current guidelines advise a “treat first, endoscope later” approach.

• Following endoscopy, GORD can be classified as either: endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD) – when a person has symptoms of GORD but the endoscopy is normal, or reflux oesophagitis – where there is evidence of inflammation and mucosal erosions.

• Further investigation is reserved for patients who fail to respond to acid suppression, rapidly relapse on stopping therapy or have alarm features.

Introduction

The occasional reflux of stomach contents into the oesophagus is a normal physiological occurrence, which relates to the transient relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter and gives us the ability to belch.1 Small volumes of ingested food and gastric acid may pass into the oesophagus when this occurs and is not usually a cause for concern. However, when the reflux of stomach contents is persistent, or causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications for the patient, it is known as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).2

Epidemiology

GORD was originally thought to be a problem of the western world, with the prevalence of GORD in Europe estimated to be between 8% and 26%.3 A review of symptoms in the community indicates that 25% of people in western populations report having GORD symptoms at least once a month, 12% report symptoms at least once weekly, and 5% describe daily GORD symptoms.4 However, this trend is now occurring worldwide, with a recent systematic review estimating that 1.03 billion people suffer from the condition globally,5 linking it to the obesity epidemic and an ageing population.6

The exact relationship between age and prevalence of reflux symptoms is unclear, but there is evidence that prevalence increases with age.7 Interestingly, studies have shown that although there is a slightly higher prevalence of GORD in women, men are more likely to experience complications of GORD (e.g. Barrett’s Oesophagus or Oesophageal cancer).8

Prevalence has also been found to be higher in smokers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)/aspirin users and patients with a raised BMI.9

Clinical features

The typical clinical symptoms of GORD are heartburn and regurgitation. Heartburn is a burning sensation in the chest, which is usually intermittent, and can be exacerbated by eating, bending, or lying down. GORD can also present with a variety of atypical symptoms such as dysphagia (difficulty swallowing); odynophagia (painful swallow); belching; epigastric pain; water brash (excessive salivation in the mouth caused by the presence of acid); and nausea.10 Patients with GORD may also experience extra-oesophageal symptoms such as chronic cough; nonatopic asthma; halitosis (bad breath); dental erosions; laryngitis; and hoarseness.2,11,12

Symptoms of GORD can have a significant negative impact on patient well-being and quality of life, through reduced enjoyment of food and physical activities involving bending, such as gardening or sport. Sleep disturbance can also occur, affecting concentration at work and resulting in reduced productivity. GORD has a significant economic burden globally, with studies estimating the cost to be approximately £760m per year in the UK alone.5

Complications of GORD

Extra-Oesophageal symptoms: GORD is a common noninfectious contributor to bronchitis, non-atopic asthma, laryngitis, hoarseness, and pneumonia.14 Due to the sensitivity of the lungs, pharynx and larynx to acid and their slow healing, traditional management of extraoesophageal GORD involved treatment with high dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for prolonged periods. However, recent studies have cast doubt on the benefit of long-term, high-dose acid suppression in these patients.15

Oesophageal strictures: Oesophageal strictures occur in approximately 0.1% of cases and are associated with white males, increasing age, and a long history of GORD.16 There is good evidence that sustained acid suppression reduces the need for repeated dilatations of the stricture.17

Fig 1. Common symptoms of GORD13

Oesophageal ulcers: Reflux commonly causes superficial erosions of the oesophagus, however a small percentage of these progress to deeper ulceration involving the muscular layers of the oesophagus. Oesophageal ulcers have a prevalence of approximately 0.05% and are also associated with white males and increasing age.16

Haemorrhage: Erosive oesophagitis has been implicated as a cause of bleeding in patients with GORD.18 Although it has been proposed that oesophagitis may be responsible for a significant percentage of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding cases,19 bleeding from erosive oesophagitis is a relatively uncommon cause for acute presentation to the hospital, but rather is more likely to present as chronic iron deficiency anaemia.20

Barrett’s oesophagus: Barrett’s oesophagus occurs in response to prolonged GORD where the normal squamous cells of the oesophagus undergo metaplasia to columnar cells which resemble the intestinal mucosa. Approximately 10–15% of patients who have GORD will go on to develop Barrett’s oesophagus, however, it is uncommon in those younger than 50 years old.21 Barrett’s oesophagus increases the risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma: Since the 1980s the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma has increased sixfold and is one of the most rapidly increasing cancers in the Western world.22 It is estimated that 1–10% of those diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus will go on to develop oesophageal adenocarcinoma within 10–20 years.23

Aetiology

The cause of GORD is likely multifactorial, encompassing a range of genetic, lifestyle and/or environmental factors.

Genetics: Genetic factors possibly contribute 18-31% to the cause of GORD,24 with evidence that reflux symptoms often affect members of the same family.5 Identical twins have been found to have a higher concordance of GORD symptoms than that of non-identical twins.26

Lifestyle: Lifestyle factors also contribute to GORD. Obesity, especially central adiposity, independent of BMI has been linked to higher incidences of GORD and related complications such as Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma.27 This is likely due to increased intra-abdominal pressure and mechanical pressure on the diaphragm increasing transient relaxation of the sphincter and increasing the risk of developing a hiatus hernia. Poor posture, tight fitting clothing and pregnancy can also cause GORD due to these increased pressures.

Smoking, alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, and spicy foods can reduce the tone of the gastrooesophageal sphincter.28 Eating fatty foods can also delay gastric emptying, leading to GORD.29

Environmental: The relationship between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and GORD is complex and not yet fully elucidated. Some studies indicate that there is a negative correlation between patients who are H. pylori-positive and GORD.30 The hypothesis is that atrophic gastritis associated with H. pylori infection can reduce gastric acid secretion and offer protection against GORD. However, other review articles state that concomitant infection with H. pylori does not alter symptom severity or treatment efficacy in those with GORD symptoms.31 Due to the strong association between H. pylori infection, peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma, guidance continues to recommend eradication of H. pylori whenever present.32

Medication-induced: Medicines that can cause GORD, or make the symptoms worse, include alpha-blockers, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, beta-agonists, beta blockers, bisphosphonates, calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, nitrates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives and tricyclic antidepressants.32

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GORD is multifactorial, involving transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and lower oesophageal sphincter pressure abnormalities. Other associated factors include hiatal hernia, impaired oesophageal clearance, delayed gastric emptying and impaired mucosal defence mechanisms. Together, these lead to the reflux of stomach acid, bile, pepsin, and pancreatic enzymes, resulting in oesophageal mucosal injury.23

GORD can be subdivided into:

Reflux oesophagitis: these patients will suffer from typical reflux symptoms, such as acid

regurgitation and heartburn. Those with reflux oesophagitis often respond well to acid suppression and show healing of mucosal erosions.22

Endoscopy-negative reflux disease (ENRD): ENRD is the most common manifestation of GORD and shows no evidence of injury to the oesophageal mucosa. Patients often have severe and atypical symptoms, and an incomplete response to acid suppressing drugs.22

The role of the community pharmacist

Community pharmacists often provide the first point of easily accessible contact for patients and are well-placed to offer initial and ongoing help for people suffering with symptoms of GORD. This involves offering lifestyle advice, using appropriate OTC medication; highlighting prescribed medications that may be an issue,33 and advice about when to refer to GP.

History taking

GORD can often be diagnosed using the symptoms described by the patient alone and therefore, a detailed history should be obtained from the patient.2 Information gathered should cover pain location, frequency, severity, timing (day or night) and duration of symptoms, as well as any specific triggers (e.g. food, on bending or lying down), and medicines that they take.

When to refer

When questioning patients with GORD symptoms it is important to recognise signs and symptoms that may require referral to their GP. Red-flag symptoms include:

• >55 years of age with unexplained treatment-resistant GORD for more than 4 weeks duration.

• Pain described as severe, debilitating or wakes the patient in the night.

• Progressive difficulty swallowing

• Persistent vomiting

• Progressive unintentional weight loss

• Jaundice

• GI bleeding (haematemesis and/ or melena)

• Iron deficiency anaemia

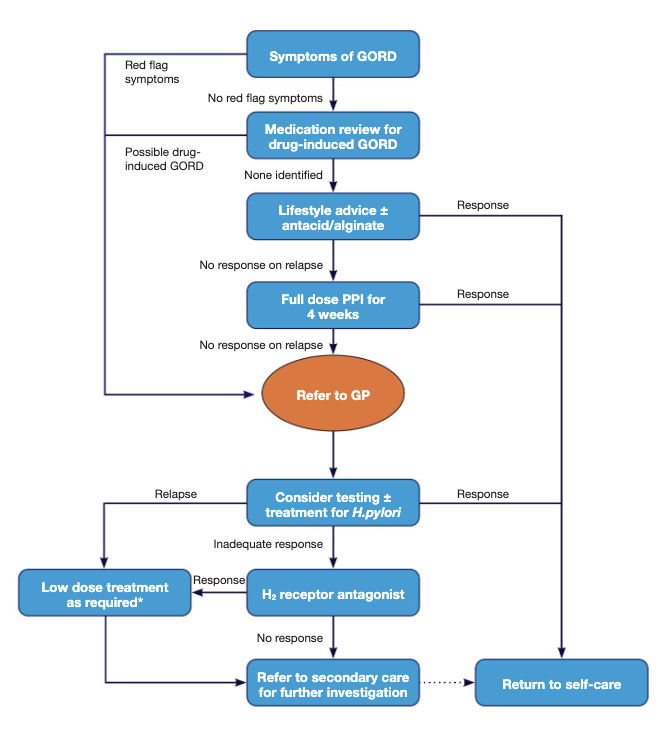

Figure 2. Management algorithm for patients with GORD. Adapted from NICE guideline [CG184]32

* If symptoms recur after successful treatment, advise patient to step down PPI therapy to the lowest dose to control symptoms, or promote the ‘as needed’ use of PPIs instead.

These red flag symptoms may be signs of serious pathologies e.g.: upper GI malignancy, peptic ulcer disease, coeliac disease, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease and coronary artery disease.22

Initial management of GORD Lifestyle advice

Simple lifestyle measures can aid symptom control.23 Smoking cessation, drinking less alcohol, and weight-loss have all been shown to help. In fact, a decrease in BMI as little as 3.5 kg/m2 leads to a nearly 40% reduction in risk of GORD, even among women with a normal BMI.34

Other lifestyle modifications that can be advised include reducing caffeine intake, having small, regular meals, taking regular exercise, and avoiding eating in the three-to-four hours before bed. GORD patients may report a trigger for symptoms such as spicy foods, citrus fruits, tomatoes, onions, chocolate and fizzy drinks. Therefore, keeping a food diary with avoidance of trigger foods may be beneficial.35

GORD symptoms can also be managed by raising the head of the bed by around 10-20cm.23 This can be achieved by placing blocks under the head of the bed or by placing a wedge underneath the mattress. Additional pillows should not be used as this tends to compress the stomach, worsening symptoms.32

There is an association between anxiety and GORD.23 Therefore, a discussion on stress and anxiety levels can be useful along with the encouragement of relaxation strategies.

Medicines known to cause or exacerbate symptoms of GORD should be reviewed, reduced, and discontinued if appropriate. This will require an appropriate consultation between the patient and GP.

OTC management

Initial management of GORD can often be achieved with antacids and/or alginates; however, longterm, continuous use of these is not recommended.33 Antacids and alginates can affect the absorption of other medications and therefore they should not be taken within one to two hours of other medicines.36

Antacids: Antacids work by neutralising the stomach acid. Their efficacy depends on the metal salt used in its composition. Sodium and potassium salts are highly soluble which make them fast acting, but with a short duration of action. Magnesium and aluminium salts have a slower onset and longer duration of action, whereas calcium salts are fast acting but also have a prolonged duration of action.37 It should be noted that calcium and aluminium salts may cause constipation and magnesium salts can cause diarrhoea.38 They are best given after food as gastric emptying is delayed in the presence of food, giving the antacid more time to work. Antacid therapy should ideally not be continued beyond 2 weeks. If symptoms have not resolved, another product should be tried, or patients should be referred to their GP.

Alginates: Alginate preparations, on contact with gastric acid, form a viscous matrix barrier over gastric contents and prevent reflux of stomach contents. They demonstrate superior symptom control to antacids. They are best given after each meal and at bedtime, or on an as-required basis.39

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): PPIs decrease acid secretion in the stomach by blocking the H+/ K+ ATPase enzyme (proton pump) within the parietal cells of the stomach. This enzyme is the final step of acid secretion into the stomach.

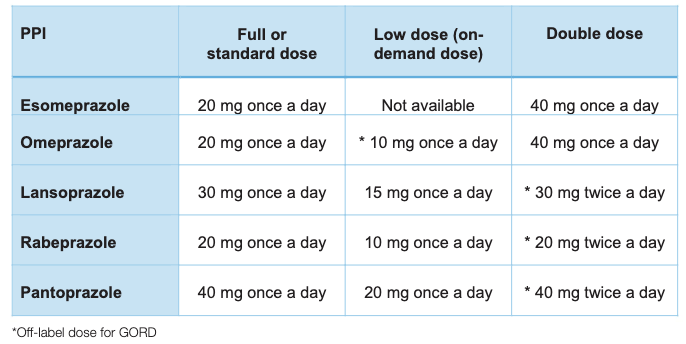

Patients with persisting symptoms of GORD, in the absence of red flag symptoms, should be started on a four-week trial of a PPI once daily as a way of confirming the diagnosis.32 PPIs should be taken 30 minutes before food, to provide optimal control of gastric pH. Acid suppression with a PPI provides effective relief of symptoms for most patients with GORD. The recommended doses of PPIs for the management of GORD are detailed in Table 1 below.

According to The Medicines Management Programme,40 pantoprazole is the preferred PPI for the management of GORD. This is due to the favourable adverse drug reaction and drug interaction profiles of pantoprazole. Pantoprazole also has a favourable cost profile in both available strengths.

NICE Guidance32 suggests that people with GORD should be offered

• A full-dose PPI for 4 weeks (or 8 weeks if they have endoscopyproven severe oesophagitis).

• If symptoms recur after successful treatment, patients should be advised to step down PPI therapy to the lowest daily dose to control symptoms. ‘Asneeded’ use of PPIs should also be discussed.

• If there is an inadequate response to a PPI, a H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) may be offered instead (Fig. 2)

Table 1. PPI doses for management of GORDTable 1. PPI doses for management of GORD

Contraindications and cautions of PPIs

PPIs are often well tolerated, with a relatively low incidence of side-effects during short term use. Adverse effects may include headache, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and dizziness. Very rarely PPIs can cause subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, severe cutaneous adverse reactions, liver dysfunction and blood dyscrasias.33

Long term suppression of gastric acidity has been linked to the reduced absorption of vitamins and minerals. As a result, PPIs should be prescribed with caution to those at risk of hypomagnesaemia (i.e. patients already receiving digoxin and/ or diuretics) and magnesium concentrations monitored. Patients at risk of osteoporotic fracture (e.g. post-menopausal women) should be advised to maintain adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D as long term use of PPIs is associated with an increased risk of fracture, especially when used in high doses for over a year. The reduced acidity of the stomach caused by PPIs permits bacterial colonisation of the upper GI tract and can lead to Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection, which can be particularly harmful in clinically vulnerable patients. Rebound acid hypersecretion may occur on stopping PPIs, resulting in an increase in reflux symptoms. To reduce this risk, PPI therapy should be tapered to a lower dose and then taken as required. Patients should be counselled about the risk and advised to manage symptoms with antacid and/or alginate use.4

To minimise the risk of side effects associated with long-term PPI use, prescribers should only prescribe PPIs when indicated, at the lowest possible dose, and for the minimum duration of time.41 Patients who require long-term PPI therapy, should be reviewed on an annual basis at a minimum.41

Patients with red flag symptoms should not be prescribed PPIs before endoscopy, as PPIs may mask the symptoms of upper GI malignancy. If the patient is currently taking a PPI and subsequently needs endoscopy, the PPI should be stopped at least two weeks before the procedure.23

Interactions

PPIs have possible interactions with a range of medications.33 These include, but are not limited to:

• Clopidogrel: omeprazole and esomeprazole can significantly reduce the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel, and they should be avoided. Pantoprazole and rabeprazole have lowest risk.

• Citalopram and escitalopram: omeprazole or esomeprazole can lead to higher levels of citalopram and escitalopram. Dose may need to be adjusted.

• Digoxin: may cause small rise in serum digoxin levels.

• Warfarin: Monitor International normalised ratio as PPIs can enhance warfarin effects.

• Methotrexate: excretion possibly reduced leading to increased risk of toxicity.

H2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs)

H2RAs reversibly bind to histamine (H2) receptors on gastric parietal cells, acting as a competitive

antagonist, thereby decreasing gastric acid secretion.42 They can be used as needed for heartburn/ GORD or taken prophylactically 30-60 minutes before known triggers, or if taken once daily, at night is best.42

Further Management of GORD If reflux symptoms fail to respond to full dose acid suppression or symptoms rapidly relapse on stopping treatment, investigations should be carried out to confirm the diagnosis of GORD.32 H.pylori testing should be considered in patients who have no red-flag symptoms, and have failed to respond to lifestyle changes, antacids and a four-week trial of PPI therapy. Other diagnostic tests performed in secondary care include upper GI endoscopy, barium swallow and ambulatory pH monitoring.

Surgery may be used in the management of medicationresistant GORD and for those unable to tolerate PPIs. The most common surgical procedure is the Nissen fundoplication, which involves wrapping a portion of the gastric fundus around the lower oesophagus. However, approximately 50% of patients managed by surgery, report the use of PPIs at 5-10 years’ followup. Consequently, long term medical therapy with PPIs may be more cost effective.43

Special considerations: GORD in pregnancy

Heartburn in pregnancy is common and triggered by hormonal changes, the enlarged uterus causing increased intraabdominal pressure, and relaxing of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Complications are rare due to the short-term nature of reflux, which usually resolves after giving birth.44

Diet and lifestyle changes along with the use of antacids/alginates should be recommended as first line. However, if a woman is taking iron supplements, antacids will interfere with their absorption, and therefore the antacid should be taken two hours before or after the iron supplement.33

Women whose GORD remains uncontrolled despite these measures may be prescribed acid suppression with PPIs. Omeprazole is clinically appropriate for pregnant women with severe or complicated reflux disease.33

AUTHOR: Fergal Garvey MPharm, MPSI

Fergal Garvey graduated with a first-class honours degree in Pharmacy from Queen’s University, Belfast in 2009. Following successful completion of pre-registration training in Northern Ireland, Fergal joined Bradlon Pharmacy Group in Drogheda where he has worked for almost 15 years. To date in his career, Fergal has worked as support pharmacist, supervising pharmacist and superintendent pharmacist for the group, and has supported dispensary colleagues in their training. His passion in pharmacy is to improve patient outcomes through health promotion and education.

References available on request

Read July IPN

Raed our latest Features